|

Juan Cruz + Luciana Martins

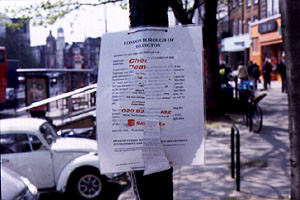

Cities are always in the making. As we go about our daily business - journeying to work, taking children to school, shopping, playing - all around us there are acts of demolition and construction, new buildings being put up, lofts being converted, shops changing their use. Some of these interventions are more visible than others, but all reflect and require a constant process of negotiation among the myriad occupants of urban space. In particular, they may well involve an encounter between those who seek to change the fabric of the built environment in certain ways, and those who in theory speak for the interests of the city as a whole - the urban planners. It is open to the entire community to be involved in such encounters, but it usually means paying more attention than we customarily do to those anonymous notices of application for planning permits which are to be found fixed to lamp-posts, gates and road signs in the vicinity of the sites in question.

Notices of application for planning permits are, like all standard forms, documents written according to certain rules, with blank spaces to be filled with prescribed kinds of information. Prior to the regulation of the act of building or of transforming a building is the discipline which must be applied to the ways of articulating desire for change. The process of informing implies in some degree the necessity of conforming. Individual aspirations are rendered into uniform chunks of information that, by their very form and register, evade certain sorts of reading. In the course of our everyday lives, we barely notice those bits of paper precariously scattered about the neighbourhood.

|

Juan Cruz's work invites us to overcome the sense of stasis, the visual inertia, prompted by the predictable form of planning permits. Wandering across the city with camera in hand, his mapping is performative; by the very act of stopping in front of a notice for a planning permit and finding the right angle/light/focus/frame in order to picture it, he is already intervening in that space. People stop to ask what he is doing, they get worried, they look twice, they wonder. Cruz also gathers up the debris associated with notices themselves, cable grips and strings left behind on walls, lamp-posts and railings after the forms have been taken or torn down. His installation tells us that he is a collector of urban aspirations, a cartographer of the trails of citizens.

Juan Cruz's mappings are works of delicacy. They don't shout. They whisper to us that there is life behind these standard forms. Peeping through these notices are fleeting intimations of intent, the minutiae of urban life, the intricacies of everyday place-making. And there is delight in wondering what is to happen next.

Luciana Martins