I have recently published an alternative guidebook to the state of California that culminates in the reader arriving at a small piece of desert land that I bought in a place called Trona near Searles Lake. The town's only employer is the mine there which belches out the by-products of its activities 24 hours a day. As a result the air is heavily polluted while the land is rich in minerals. It is a fascinating place, a bit like the Simpsons gone wrong.

Jeremy Deller

|

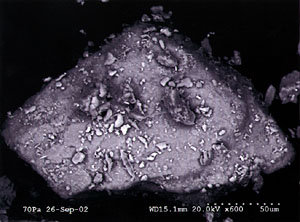

General electron microscope image of sand grain

A single grain of sediment from Trona has been analysed using a Scanning Electron Microscope. The grain has an a-axis greater than 200Ám and a b-axis of 120Ám indicating that it is a very fine sand grain. It also has grains of silt and clay adhering to the outside of the grain. The edges of the sand grain are sub-rounded. The elements associated with the sand grain show high Silica (Si) and Oxygen (O) values but also relatively high Aluminium (Al), Sodium (Na) and Magnesium (Mg) peaks. On the elemental map of this grain, these elements are primarily associated with the sand grain indicating that it is a Feldspar grain. In addition, some of the smaller grains show concentrations of Calcium (Ca) and Iron (Fe), probably Calcium carbonate and Iron oxide respectively .

The feldspar sand grain has been eroded or weathered from the Mesozoic bedrock intrusions in the local catchments or from the Sierra Nevada and transported into Searles Lake basin in the Trona area. The weathering or erosion processes (such as glacial erosion) probably created an angular shaped feldspar grain. The grain was subsequently modified to its present sub-rounded form by collisions with other minerals in the suspended load or bedload of streams and rivers. The grain is deposited with smaller grains, suggesting mixing of the sediment during deposition maybe at the margins of the lake or subsequent reworking of the primary deposit.

Adrian Palmer

|

Satelite photograph of Trona

Trona, California lies in a basin surrounded by the Argus Mountain range to the west and the Slate Mountains to the east. The town is situated on the northwest margin of Searles Lake, which formerly covered an area in excess of 50 km2 10,000 years ago at the end of the last glaciation when water was supplied by glacial runoff from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the west. Presently, Searles Lake has relatively small catchments draining water from the Argus and Slate Mountains, with the main streams and rivers draining from the north and south. At the present day there is little water in the lake due to the evaporation of what little precipitation falls in the Mojave Desert. The high evaporation rate concentrates minerals such as salt, allowing it to be used as a mining resource. In addition 98 of the 104 known elements can be found in Searles Valley, derived from the Pre-Cambrian and Cambrian rocks and intrusive Mesozoic rocks, which are found in the vicinity.

Adrian Palmer

|

Human Trona

Trona is a hundred and twenty miles north of Los Angeles - three hours drive or so. But there's no point in going there. In the Michelin guidebooks attractions are rated as 'worth a journey' (***), 'worth a detour' (**), or just plain 'interesting' (*). In a Michelin world, Trona isn't worth getting out of bed for. Even the local Californian realtors don't try that hard to talk up the attractions of the place - the Trona Pinnacles national natural landmark (a few oddly shaped vertical rocks in the desert), the Searles Dry Lake ('source of pink, peach and cranberry halite'), and the site where some of the battle scenes in Planet of the Apes were filmed (no, not the Charlton Heston original, but the Helena Bonham-Carter remake). If Trona stands out, it's for qualities not usually seen as tourist attractions. If Michelin gave rosettes for heavy metal pollution, or for burnt-out cars, Trona might be in the running.

But not even nowhere is content to remain unremarkable - in the twenty-first century all places strive to be at least worth a detour. Trona has its own local civic society - 'Trona Care' - with suitably lofty aims:

'Our purpose is to improve Trona and bring the town back to one that has pride. Where everyone can feel safe and be proud of where they live. Working to clean up and beautify the town of Trona, improve property and bring our property values up to what they were assessed for, by the county tax assessor.'

Perhaps more significant than such self-conscious attempts to make Trona into a 'point of historical interest' is the way that sites that are worth a journey seem to spring up spontaneously from the desert sands - a giant cowboy boot as a headstone (or should that be footstone), or a shrine to the victims of death by drunken driving.

And here is Trona as the final destination in a new guide to California. Well, not Trona exactly, but five acres of land outside of Trona in the Mojave Desert, the back of the back of beyond. Five acres of land bought by the artist at auction, and enshrined as the roof-of-the-Sistine-Chapel, the top-of-the-Empire-State-Building of this particular Californian tour. It's the ultimate souvenir. Better than an Eiffel Tower snow-shaker, a plastic Taj Mahal. Better even than a lump of Soviet-era asbestos from the Berlin Wall - see the place, then buy the place. And now, via the Sediment Laboratory at Royal Holloway, University of London, is a souvenir of a souvenir - a sample of sand (we could get technical here - but sand is a pretty good working description). A sample of sand in all its 'inchoate' glory (and you wouldn't expect anything less from the very cheapest end of San Bernardino County).

This could all be anti-tourism, a parody of the commodification of place by the tourist industry. After all the history of anti-tourism is as old as the history of tourism itself - as soon as there were people to pay to go to places, to buy, read and follow guidebooks, there were others (artists and intellectuals as chief perpetrators) to call them mindless dupes. What better way to celebrate modern tourism than to send people on a journey to a patch of nowhere.

Or this could be just more tourism - another ride in the great American theme park. No society in the history of the world has been better than the USA at glamourising its ordinary places, its 'non-places'. And no part of the USA has done this more consistently, or more intensively, than Southern California. The shack in the desert, the one-horse town, the solitary filling station on the long straight road are as familiar sites in global popular culture as Big Ben or the Great Wall of China. This is road movie as guided tour, a pre-packaged existential odyssey, ending at your own customised 'Big Tuna' (population 104).

Or perhaps this is hyper-tourism - a tour in which the experience of tourism becomes more important than the specific qualities of any of the sights themselves. Travel writers have long separated themselves from mere tourists through claims of spontaneity, of the detailed observation of difference, and of the creative engagement with new places. Yet strip away the blunt imperatives of guided tours or guidebook lists of must-see sights, and these are central experiences of tourism too: the chance meeting or holiday romance, and the ways that the apparatus of ordinary life - light switches, electricity sockets, bath plugs, coins - suddenly become objects of scrutiny. When we examine beach sand running through our fingers on a long hot summer afternoon it's like an amateur version of this professional analysis of this Mojave sand. With time on our hands, we subliminally measure the physical qualities of the sand - its rate of flow, its moisture quantity, the colours of its grains. It becomes interesting*, perhaps even worth a detour**. And perhaps this is where the tour takes us - not to a non-place, an empty square of hot sand, but to a heightened awareness of the ways we engage with places.

David Gilbert