|

Case

Studies

(Landing, a work-in-progress exhibition)

Walk into the entrance lobby of most university geography departments and

you'll see one or two display cabinets. Heavy wooden or metal containers

showing the results of the department's research, their books and papers

are glassed over beyond reach and careful scrutiny. Their display is usually

of a rather muted kind - it's their presence that's important, not the details

of what they hold. They are there to materialise the labour of research,

its productivity, its results, its weightiness, and not its discoveries.

You are meant to notice that the cabinets exist, but not to look at their

contents in any particularly sustained way. All the more so now, since the

assessment of a department's academic output takes place through the quasi-objective

procedures typical of audit culture. The books and papers in academic display

cabinets, never subject to many interested gazes, now languish in even greater

obscurity, relics of another era.

Which

is why, perhaps, many visitors to this exhibition simply did not see it

on their arrival. Its site, in the two display cabinets in the Geography

Department's entrance lobby, did not encourage visibility. White walls,

but no frames, no captions, and too many easy chairs. It didn't look like

an exhibition. But then, nor did it look much like an academic display cabinet

any more. Only one book remained as a forlorn reminder of past use - and

even that was a cookery book, recently elevated to being a fit subject for

geographical research but still not yet acceptable as an output of geographical

work (I await the day). Nonetheless, one has to look at something while

hanging around in a lobby, and these cabinets do exert their own pull. Not

just showcasing the fact of academic labour, the pieces, each occupying

one quarter of a cabinet, engage rather carefully with the processes and

sometimes with the politics of producing and displaying knowledge about

our environments. Unlike the cabinet's brute marking of the output of academic

work, the exhibition focuses on the processes of that labour. A casual glance

at their container thus becomes something more sustained. The actuality

of the cabinets' existence becomes supplemented by their temporary conversion

into a somewhat more reflexive exhibition.

Let's

return to that relic book. It's a dog-eared copy of Elizabeth David's classic

Italian Food. Spilling out of it though are Richard Wentworth's photographs,

brash in their newness and kodak brightness. Phil Crang's text makes this

juxtaposition an invitation to look beyond the conventional and the canon,

beyond the rather tired book, and to see the marginal and its detail as

inventively exciting, 'the peeling paint and the foil' of a take-away shop.

The photos are of cheap cafes and greasy spoons, selling food from many

places and from mass-produced no places, and Crang celebrates the texture

such everyday locales give to our lives. Both the text and the book/ photographs

also entice us to look. There's a suggestion that the visual may be a resource

that academic books are not good at engaging with. If the David stands in

for the ghosts of the books which usually inhabit these cabinets, then the

photographs are the brash newcomers which may startle those books from their

complacency.

|

The

collaboration between Jeremy Deller, Adrian Palmer and David Gilbert also

considers the relation between the written and the visual. Here we see a

sample of soil brought back from Deller's plot of land in California to

the soil laboratory in the Geography Department, and we see it twice. We

see the sand and grit spilling from a plastic container and we also see

it magnified hugely and photographed. Deller writes a brief caption emphasising

his fascination with his piece of land, but we are left wondering at the

precise nature of that fascination, staring at the soil as if in its nature

it held the answer. The soil is really there, in the cabinet, and its complexity

is described - and description it does indeed seem to be - by the photographs

and their scientific genre. But it does not speak, and so we turn to Gilbert's

essay which seems by contrast so much more informative, not so say seductively

eloquent. We learn about modern tourism, anti-tourism, and hyper-tourism

in a way that renders that soil even less interesting - though no less real.

Here the text serves again to suggest a difference between writing and seeing,

except that this time the text butts up against what is visible, and the

visible soil is all the more intransigent for its silence. What we can see

here, then, is installed more as the limit to what is knowable and less

as a resource for new kinds of knowledge.

|

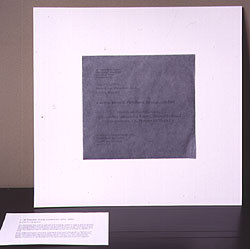

Elsewhere

in the cabinet, though, the relationship between seeing, writing and the

environment is approached in rather more complicated ways. In these pieces,

text and vision are less obviously counterposed, and knowledge is made somewhat

more uncertain as a result. Jacqueline Jeffries, in considering the work

of physical geographer Rob Kemp, has produced a piece altogether more enigmatic

about the relation between knowledge and seeing, writing and the earth.

As Jeffries explains, the addresses she has redrawn on paper are the addresses

of soil suppliers. Her own garden's soil has been covered with concrete,

and in buying bags of compost for planting she has found that soil easily

moves. It is transported long distances and, presumably, given the popularity

of gardening now, in huge quantities. Earth then is no longer quite the

stable foundation it sometimes seems. Unlike Deller's soil, though, Jeffries

does not think of hers as mute. Instead, she makes it speak, by mobilising

it to write. For she uses graphite, a rock, to draw the addresses. The addresses

are legible; the earth is made to write and to produce knowledge of itself.

This is not a simple assimilation of the soil into language and knowledge,

however, for Jeffries has also veiled her paper in a very fine network of

lines. The addresses are legible, but from certain angles, only just. They

emerge from the graphite but appear also to be vulnerable and disappearing

back into it. Soil here then sits on the cusp of the visible and invisible,

the knowable and the unknowable.

|

One

of the cabinet's quarters appears very much as a geography display might.

An OS map with CD of Barra, in the Outer Hebrides, wrapped in rain-proof

plastic cover, represents a project to be realised after this work-in-progress

exhibition. The map of Barra is here as walking guide and prelude to the

collaboration between Jean-Luc Schwenninger, Matthew Dalziel and Louise

Scullion that explores the traces of long term change in the landscape of

Barra in the field and on film. The map's picture repeated on the CD suggests

the process of seeing and converting this place to map and other forms of

representation.

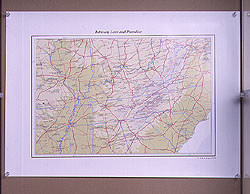

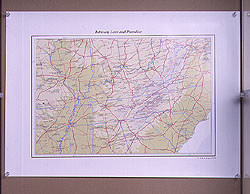

Kathy

Prendergast's map also hovers on that edge between knowing and unknowing.

At first glance, this is simply a map with the place names changed. Its

layout looks familiar (its base is the eastern seaboard of the United States),

there are lines for roads and rivers and different colours to mark the land's

contours. But the names are new: Hope Hollow, Liberty, Needy Creek, Paradise

Park, Hopeful. This would be enough, since the new place names are wonderfully

evocative of an emotional geography of relationship, and Catherine Nash

makes a connection to the feelings immigrants to a new land might have.

But the names are repeated many times, sometimes with slight variation -

Paradise, Paradise Park, Paradise Falls, Paradise Creek - suggesting a repetition

of structures of feeling that is at once intensely moving and somewhat banal.

Hope Swamp - my favourite, how marvellous; Hope Fork, Hope Falls, Hope,

Hope, Hope - how unimaginative. But if the repetition problematises the

register in which an emotional state is being named, the map also problematises

the place to which the name is being attached.

|

Many names have a red dot beside them indicating (you guess) a settlement,

but many do not. They are names that hover, seemingly unattached, over a

blank space in the map. Or the name seems not to correspond to whatever

features the map does show: Dams and Creeks have no water nearby, Hills

have no high land indicated. Then again, other features on the map are unnamed:

rivers, roads. And the map lacks those fundamental signs of accuracy that

every schoolchild is taught: a key, a scale and a pointer to north. Here

then, our knowledge of the land this map shows us is quite disorienting.

It is not an objective and accurate map, at least not as we usually understand

that kind of map to be, yet its emotional subjectivity also seems somewhat

unreliable. Most puzzling of all, the relation between name and place is

so uncertain as to suggest, in the end, arbitrariness. Our relation between

ourselves and an environment is rendered uncertain.

|

Some

elements of this installation explore how and what we can know about environments,

whether that be through writing about them or visualising them. In so doing,

they render the cabinet and its limits problematic. The cabinet obscures

such an exploration in its preference for the display of academic product,

not process. These pieces therefore render the cabinet more like an exhibition

than do some others, I think. Some of the other pieces here prefer to invoke

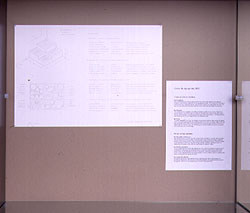

the weightiness of the cabinet more directly. Nils Norman and Vandana Desai,

for example, do so in their showcasing of designs of objects that could

further sustainable development. Here the academic authority envehicled

in the cabinet is put to use to advocate sustainable architecture. Although

advocacy is certainly a new purpose for the academic display case, it still

has some relation to the authority of the academic expert. So the designs

for an office unit, a work unit and a street water kiosk resonate with applied

relevance; as Desai says, "our main concentration is on the theme of sustainability,

affordability and low cost maintenance for poor people". Yet here too, the

authority is not quite what it seems, the expertise not quite watertight.

For the designs are somewhat whimsical, not only in the idealism of their

politics but also in their technical accomplishment. They carry minimal

technical details - they are ideas visualised not working plans, inspirations

not instructions.

|

Jan

ice

Kerbel and Felicity Callard also use the cabinet to advocate, but also seem

to slip between genres, disconcerting the cabinet's framing. Their plan

for an indoor garden for agoraphobes carries more information and recommendation

than Norman and Desai's diagrams. Kerbel's plans and lists suggest what

plants to use, what their preferred environment is, the size of the garden

area, where to plant what. It's detailed and authoritative, despite its

rather faint execution in pencil. The printed text, though, where Kerbel

and Callard outline the principles underlying the garden, has rather disconcerting

overtones of the garden makeover programme as well as the academic expert

("high ceilings will appear lower if you use hanging baskets, low rooms

will appear higher if you use bold and upright plants"). The notion of a

visit to a garden centre as actual shopping therapy would be whimsical if

it were not the case that the users of these indoor gardens precisely cannot

shop for or in comfort of any kind. The display cabinet as holder of authority

is thus somewhat undermined, both by the reference to other kinds of gardening

and to the impossibility of that reference if the garden were to be created

by those for whom it is intended.

|

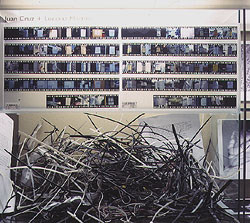

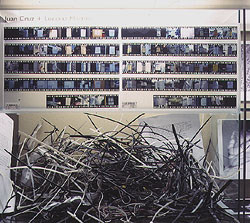

The

final installation is from Juan Cruz and Luciana Martins. It is the only

one to directly comment on these cabinets, and does so in its text (print

outs of email correspondence), in its images (included is a 35mm transparency

of the cabinets themselves displayed) and in its installation (the transparencies

are illuminated by the integral toplighting of the cabinet). Many of the

relations to the cabinets to be found in the other installations are reiterated

here. The slides show the notices put in streets when planning permission

to change some aspect of the built environment is sought. Below them, an

untidy pile of cable clips and bits of string have been dumped, it looks

like the means by which the notices were held in place. And being 'in place'

is what this piece explores. As Cruz notes in one of the texts, planning

permissions demonstrate an investment in a place through a desire to change

it. I find this assertion fascinating, since it is so often assumed that

to feel in place is to know it fully and to want it to stay the same. But

the engagement with place through various strategies of change or of not

knowing is a theme of many of these installations. Maps that are uncertain,

earth that moves and is silent and speaks, changing a house where constancy

is valorised (the agrophobe's garden), alterations in what we see in the

everyday, diagrams that don't work - we have seen all these. The mess and

complexity this paradox between knowing and not-knowing a place produces

is materialised in that jumble of cable and string, a jumble which resists

the order of the cabinet, its lines of tidy books and papers, its squareness

and its weight. The cable and string seem to epitomise the way this exhibition

pushes at the boundaries of its display cases, suggesting the possibility

of other ways of knowing.

The supplementarity between the two modalities of this installation - between

the mode of the display cabinet and that of the exhibition - is not resolved

by any of these pieces, then, and is if anything heightened by their juxtaposition.

The careful scrutiny invited by the exhibition vies with the authority of

the display cabinet, and each piece negotiates this relation in its own

way. Even those that do not refer directly to academic modes of display

still make use of the glass and the frame to articulate the gaze of their

spectators. In the end, then, what this exhibition suggests - and this is

salutary to those in the social sciences who wish to rush headlong into

visual arts as if they offered an answer to what seems increasingly like

the dead end of representational theory - is that both these modalities

rely on quite particular modes of address but that make a demand that is

both authoritative and productive. The exhibition demands its own way of

seeing, just as much as the display cabinet. Its focus may be different

but its power is not.

Gillian Rose |